MORE TIME, BETTER HITTERS

TAKING A STEP OR TWO BACK

When life throws us a curveball and we need to make a difficult decision, a great response can be to step back, give it a second thought, and then make the decision. As we all know, this approach allows more time to process the decision, and though not always, more often than not, the extra processing time leads to better decision-making.

The same can be said when it comes to baseball, specifically hitting, where batters have just milliseconds to decide if they should swing at a given pitch or not. These pitch-by-pitch decisions have a massive impact on the outcome of a game.

Ted Williams, one of the great hitters of all time, was very clear in that he believed the number one thing a hitter must do, with less than two strikes, is to get a good pitch to hit - a pitch that the hitter can hit relatively hard. One of the greatest, smartest hitters ever is saying the number one thing a hitter must do is first get a good pitch to swing at. Much easier said than done.

The more time a hitter gets to see the pitch coming in, the more information they’ll have to make an accurate decision as to whether it’s a good pitch to swing at or not. I highly recommend that hitters buy themselves as much time as possible by moving as far away from the pitcher’s release point as the rules allow. Make hitting easier and buy more time.

DEFAULT SETTING

I recommend hitters have a default setting, a default position, of placing their back foot on the back line of the batter’s box closest to the catcher and giving the hitter an extra 1-3 feet, depending on the hitter’s original position. On a 50-foot mound, a hitter that moves 2 feet further back toward the catcher gets 4% more time to see and hit the pitch, giving hitters more time to decide whether the pitch is worth being swung at accurately.

Take a few minutes after reading this article to search the internet for photographs or videos of your favorite hitters in the major leagues, and look closely at where their feet are when they are in the batter’s box. 99% of the time, the back foot is touching the line closest to the catcher. In fact, many of the great hitters have part of their back foot outside of the chalk line. Many of you have seen hitters actually dig out that back chalk line because that is where they want to position their rear foot.

If you look closely at the back chalk line of the batter’s box at a major league game, by the end of the game, or even just halfway through the game, that back line will have been completely dug out, and there really isn’t much of a line left.

WELL INFORMED

Whether MLB hitters are trying to put a good swing on a firm fastball or accurately decide whether or not to swing at a breaking ball that has good depth, they clearly understand the value of gathering more information about a pitch before having to choose to swing or not. We all know that if a hitter doesn’t swing on time, success at the plate will likely never occur, even on the slowest pitch. Hitters have to swing by a certain point if they want to make contact and hit the ball in fair territory. With 2-strikes, it’s a little different because foul balls are considered a decent result, but with less than 2-strikes, hitting foul balls is not nearly as desirable.

A TRADE WORTH MAKING

Some advanced coaches and players may have some thoughts as to why moving back in the batter’s box may make some aspects of hitting more difficult.

I understand that, for example, a low strike may become a harder pitch to hit or that moving back in the box may, geometrically speaking, shave off a few degrees of fair territory. These are valid concerns, though I strongly believe the tradeoff makes moving all the way back in the box well worth it.

Moving to the back of the box helps the hitter on every single pitch. While those examples of concern just mentioned, will only show up intermittently from time to time, and maybe not for a few at-bats or even games. However, a hitter who has more time on every pitch to decide whether or not to swing will net a larger benefit even after the tradeoffs are weighed.

Another opposing comment I commonly hear is, “Well, Coach Bo, those examples you’re telling us to go look up are Major League players, and I’m coaching 11-year-olds.” My response to that is, “It’s all relative.” The speed of the pitches is faster for those major league hitters, but those major league hitters swing a heck of a lot faster than the typical 11-year-old. With mound distances factored into the equation, a 72 mph Little League fastball is equivalent to a 95 mph Major League fastball, and then factor in the strength and swing speed of college and MLB hitters. It starts to become clear that it’s a very even comparison. If the best of the best do it, and the task is relatively similar, all things considered, then I believe youth hitters should look to follow this strategy.

SLOW-MO

“Now, but Coach Bo, what about those extremely slow pitchers? You know, those soft tossers? Should we still be in the back of the box when facing those guys?” Okay. Okay. You got me there! Yes, against extremely slow pitchers, I would recommend moving up in the box and setting up more in the middle, but not all the way to the front of the box. When I say slow, I mean extraordinarily slow. Moreover, the best way to adjust for extremely slow pitchers is not necessarily to move up in the box but rather incorporate extraordinarily slow pitches into your batting practice routine, especially if you know that a really slow pitcher’s coming up on the schedule.

If we are not already varying our batting practice pitch velocities, then we are doing our hitters a big disservice because we are not replicating ‘game-action’ during practice. Of course, pitchers have various speeds, and I think it’s important that we adjust batting practice to match some of that variation as best as possible.

I recommend that every once in a while during batting practice, randomly throw an extremely slow pitch or an extremely slow breaking ball—work to keep our hitters disciplined, learning to wait back on those really slow pitches. Think about the great pitchers like Mark Buehrle and Tom Glavine, who both made a living out of carving up hitters with slow stuff simply because hitters couldn’t adjust to their speed. Before they knew it, the game was over, and they were 0-4 with 2 strikeouts and a few weakly hit ground balls. That’s why Mark Buehrle could go out there and throw a perfect game, throwing 84 mph. They both threw average high school fastballs and average high school breaking balls, albeit they had good change-ups but nothing that appeared remotely dominant.

Even the great Greg Maddox got better by throwing slower. I believe a lot of that’s because we don’t train hitters in batting practice for that uniquely slow velocity, and not necessarily because hitters are too far back in the batter’s box.

And I understand that because most of the guys you face at every level will not be throwing extremely slow or quite a bit slow. They’re not going to be an outlier necessarily. They might be like fringe slow, but that’s not necessarily enough to really, you know, adjust your batting practice routine completely.

TERABYTES VS MEGABYTES

Going back to the comments I hear when I discuss this with coaches is, “Coach Bo, those guys are Major League hitters facing Major League pitchers, facing 100 mph fastballs.” However, the average fastball in the major leagues is about 94 mph; it’s not 100 mph, and while Major League hitters may have slightly less time to react to the typical pitch, it’s fairly similar when distance is factored in, but that still doesn’t tell the whole story. Major League hitters have a considerable advantage over younger players. Stay with me here. They have a significant advantage by having a knowledge database of tens of thousands of pitches.

Derek Jeter stepped into the batter’s box with an SSD (solid state drive) in his brain containing 20 terabytes of experiential pitch information, while youth and amateur hitters are stepping into the batter’s box with more like a gigabyte USB flash drive. That’s not a knock on youth players; it’s just reality. Derek Jeter and these major leaguers have seen thousands and thousands and thousands of pitches. They have that experience of seeing a mega amount of pitches, and that information has been collected, stored, and ready to use, giving them a huge advantage over youth players. Yet they’re still digging into the back of the box.

NOW THAT WAS PRETTY LOW

What if the pitcher throws many pitches to the bottom of the strike zone? Wouldn’t moving up in the box make it easier to hit those low pitches? Again, how many times does a youth hitter have an at-bat in which the pitcher throws three perfect pitches at the very bottom of the strike zone? Rarely, if ever. Having a strategy based on something that rarely happens is not a solid plan. Also, moving back in the box allows the hitter to comfortably reach those lower pitches if and when they do come.

Moving back in the box may lower the pitch while it’s in the hitting zone, a few inches, not feet. I don’t think that’s going to make a huge difference when hitters move back a few feet. Even the great Captain Jeter, who was strong, athletic, and could handle pretty much any pitch velocity, still kept his back foot on the back line.

Now, like the great Jeter, have your hitters go dig out the back chalk line and give themselves the best chance to be successful hitters. Coaches, give your hitters the opportunity to have more time to make a game-changing decision. Throughout the season, this adjustment is going to yield a big net benefit.

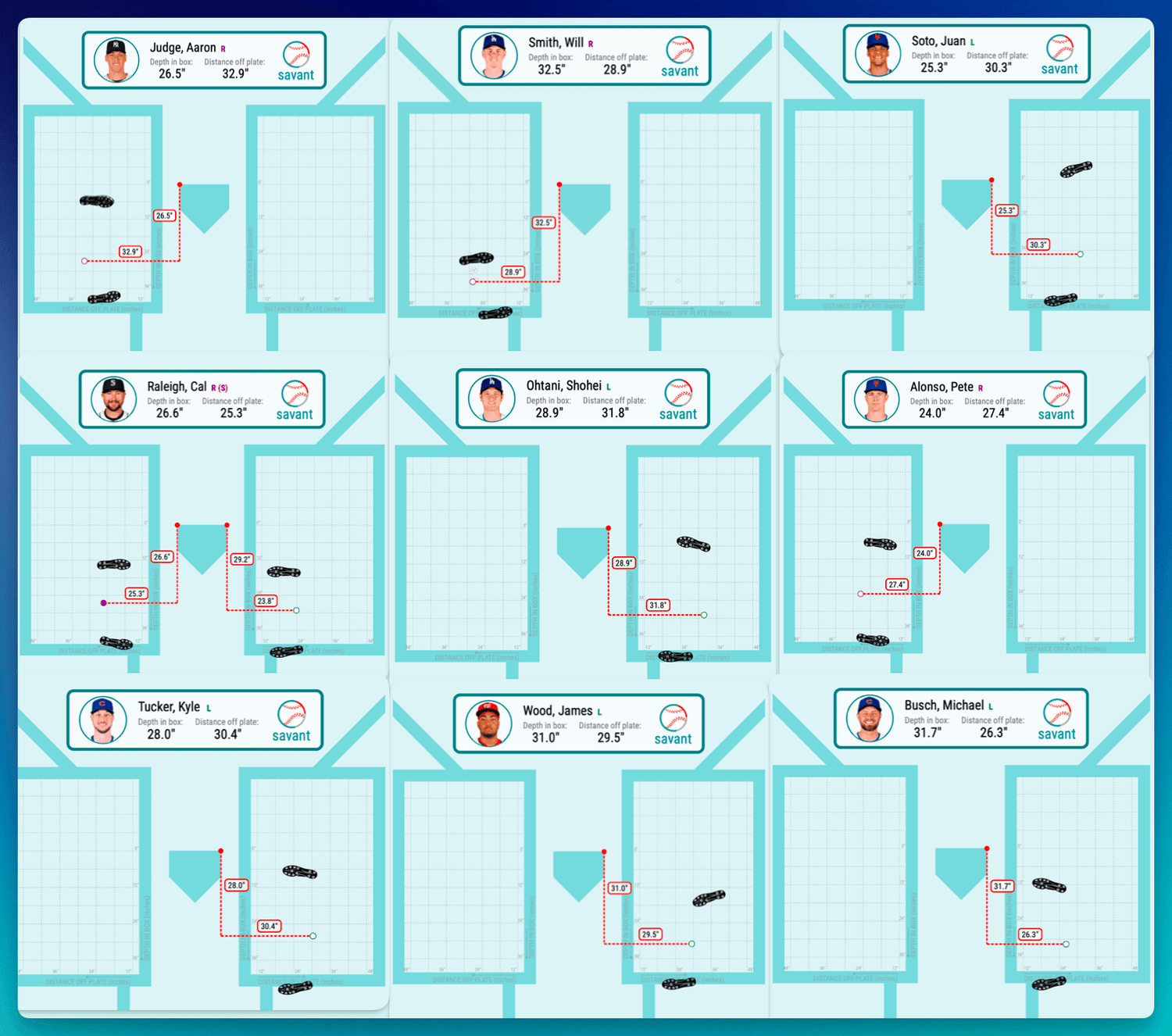

The diagram below shows where 9 of the top 10 hitters in 2025 (as of July 9th) set their feet before they start their swing.

What's the one commonality?

(per Baseball Savant)

By: COACH BO

Audio version of this article: CLICK HERE

Photo Credit: Neonbrand (Unsplash)

©2026 - 8020BASEBALL